Branch Rickey was able to step up to bat for Jackie while he was being torn apart in the papers. Rickey stated that “Jackie’s the same high-class boy he was the first year we brought him up. He’s entitled to all the rights of any other American citizen. He’s a great competitor and resents any violations of those rights” (Rampersad; 207). In response to Lacy’s attacks on the Dodger and Robinson’s occasional out bursts, Rickey retaliated saying;

“Perhaps he has lost his temper occasionally the same as any white player would do. But he’s been sorry for it afterward and has used good judgment. We couldn’t have picked a finer boy than Robinson for our experiment of introducing a Negro into organized baseball” (Rampersad; 207).

Robinson was under a considerable amount of stress at the time. The hate mail, death threats, being in the nation’s spotlight, constant badgering from the press, and being “broken into the league” with high and inside fastballs all began to take their toll on Jackie. In an interview with Robinson biographer, Arnold Rampersad, Rachel Robinson (Jackie’s wife) began to worry about Jackie’s well being;

“In those months, according to Rachel, Jack’s worries ‘were eating at his mind, for he would jerk and twitch and even talk in his sleep, which was not like him.” Sometimes he would raise his voice in anger, but anything more violent was out of the question.

Aware of his ordeal, she tried hard to make their home a haven, which Jack appreciated; he had little interest in going out with the boys.” (Rampersad; 180).

Robinson’s standings with the press would eventually change dramatically, and with surprising

outcomes. Called upon by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1949 to refute statements made by Paul Robeson, one of the most admired and famous blacks of his time. Robeson was addressing those who attended a gathering of the leftist World Congress of the Partisans of Peace at the Salle Pleyel in Paris when he “had uttered the most controversial words. ‘it is unthinkable,’ he allegedly declared about the United States and the Soviet Union, ‘that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind” (Rampersad; 211).

outcomes. Called upon by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1949 to refute statements made by Paul Robeson, one of the most admired and famous blacks of his time. Robeson was addressing those who attended a gathering of the leftist World Congress of the Partisans of Peace at the Salle Pleyel in Paris when he “had uttered the most controversial words. ‘it is unthinkable,’ he allegedly declared about the United States and the Soviet Union, ‘that American Negroes would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against a country which in one generation has raised our people to the full dignity of mankind” (Rampersad; 211).Branch Rickey set up an “invitation” from the House Un-American Activities Committee so that Robinson’s growing voice could be heard. Robinson explained to the Committee that in no way did he consider himself an expert on communism or any other type of political organization. According to an article that ran in the New York Times, Robinson did “ask to be put down as ‘an expert on being a colored American, with thirty years of experience at it.’ ” (Trussell; 1). Robinson quickly took the opportunity to denounce racism, many years before the advent of the Civil Rights Movement. Robinson was able to convey to the Committee his love for his country and his willingness to defend it.

Despite his efforts to appear patriotic and expose the racial inequalities his people faced, the remarks against Robeson were what caught the attention of the press and the American people;

“I’m not fooled because I’ve had a chance open to very few Negro Americans,” stated Robinson. He vowed to continue fighting racial discrimination in sports and other areas. At the same time, Robinson rejected Robeson’s assertion that blacks would not fight for the United States;

‘I’ve got too much invested for my wife and child and myself in the future of this country, and I and other Americans of many races and faiths have too much invested in our country’s welfare, for any of us to throw it away for a siren song sung in bass” (Tygiel; 334).

The “siren song sung in bass” Robinson was referring to pointed fingers at Robeson. Robinson believed that Robeson was “shooting from the hip” in his remarks, and felt that his (Robeson) voice did not speak for the entire African American race. Members of the press, however, focused on Robinson’s criticism of the African American Icon, rather than what Robinson had hoped to shed light on; racism in America.

The press, after the Robeson bashing, began to take sides; the white press began supporting Jackie, while the black press remained critical of its bright star. The New York Post ran parts of his speech to the Committee under an editorial entitled “Credo of an American”. The Daily News, ended its editorial piece on the event with ‘Quite a man this Jackie Robinson. Quite a ball player. And quite a credit, not only to his own race, but to all the American people” (Rampersad; 215).

A New York Times article reported that a Democratic Representative from New York, Arthur G. Klein, proposed “that Congress print 500,000 copies of a statement made July 18 before the House Un-American Activities Committee by Jackie Robinson” (No Author; 39). Klein said in a letter to Representative Mary T. Norton (D-New Jersey, chairman of House Administration Committee) “This great American athlete has spoken successfully for all minorities-and for all Americans” (No Author; 39).

The black press was more critical of Robinson; they felt as if he had become a puppet for the white press. They felt as if Robinson was playing into their hands, or buying the white press’ agenda. “To the New York Age newspaper, Harlemites were split sharply on the issue. Robinson had come back from Washington, ‘in the duel role’ of leader of his race and ‘handkerchief head’ ” (Rampersad; 215).

What Jackie didn’t realize was that in negating Robeson’s remarks and by testifying against him, he destroyed what respect and admiration any blacks had left for the influential Robeson. The House got exactly what they wanted from Robinson; a way to remove the “un-American Activist” from public light.

Some members of the black press, like the Baltimore Afro-American, felt that Robinson did more to spearhead a movement against racism then to knock Robeson’s communist remarks; “The Baltimore Afro-American reported that HUAC’s maneuver in summoning Robinson had ‘boomeranged’, in that he had been much more severe on racism that communism. Its headline read: ‘Jackie Flays Bias in Army’ ” (Rampersad; 215).

Throughout his first three seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson was constantly in the nations spotlight and forever a target of the press. His every move, every word, every breath, was under constant watch by both the white and the black press. Living under these conditions took its toll on Robinson, and he would need an outlet off the field to vent his frustrations. One would imagine that Robinson could find a type of peace on the baseball diamond, but the stands, filled with bigots, hatred, and racism only added to the discomfort that came with being a pioneer. In his essay “The Greatest Season” Roger Kahn wrote of a visit he had with Robinson, shortly before his death;

“Before his death, I was visiting the Robinsons in North Stamford, Connecticut, and Mrs. Robinson,Rachel, whom we call Rae, said, ‘No single reporter, not one has ever asked me this. If Jack had a hard day at the ballpark, if the bigots were yelling at him, did he take it out on family when he got home? He didn’t,’ she said. ‘The only way I could tell was that he’d take a bucket of golf balls and his driver and start hitting them off the back lawn into the lake.’ Then Jack looked at me and his eyes were twinkling. “The golf balls,’ he said, ‘were white’ ” (Kahn; 42).

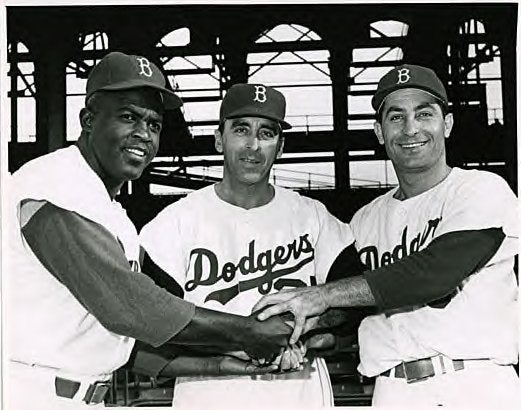

Jackie Robinson set out to do the impossible; he was going to break down the color barrier that cast a dark shadow over America’s pastime and he accomplished that task with the utmost candor and respect. He blazed a trail for the likes of black superstars of the future. Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente, Sammy Sosa, and for those who follow in his path, all owe an infinite amount of gratitude to Robinson.

Hank Aaron once said “I hope black kids today can learn what Jackie went through, what I

went through when I started, what all of us went through. Now there is a statue of me outside the stadium in Atlanta. When you think about it, that statue is as much a tribute to Jackie as it is to me. You don't hear his name much anymore. I think people have forgotten. Baseball should do something about that. Baseball owes Jackie Robinson something” (Allen; 199-200).

went through when I started, what all of us went through. Now there is a statue of me outside the stadium in Atlanta. When you think about it, that statue is as much a tribute to Jackie as it is to me. You don't hear his name much anymore. I think people have forgotten. Baseball should do something about that. Baseball owes Jackie Robinson something” (Allen; 199-200).On April 15, 1997 Major League Baseball retired Jackie

Robinson's number. In every stadium throughout the league, the Number 42 is proudly displayed, in honor of Baseball's Greatest Experiment.

Robinson's number. In every stadium throughout the league, the Number 42 is proudly displayed, in honor of Baseball's Greatest Experiment.Ten years later, on the 60th Anniversary marking Robinson's entry into baseball, Robinson was again honored, this time, by having every player in the league don his number.